Sound Bite

Francis Bacon was linked to the play The Merchant of Venice in a book published in 1965. No one has ever challenged, or further explored, that assertion. Now Christina Waldman, JD, has utilized modern research tools to examine clues from within the play itself, the works of Francis Bacon, and legal history to explore the connections.

She shows how the trial scene shifts from a "law court" to "chancery court," presaging an important evolution of the English legal system that Francis Bacon had long been quietly advocating, and she has turned up countless suggestive examples of word-play along with intriguing possible historical precedents for names and symbols used in the drama, adding layers of appreciation and pleasure to the reading.

About the Author

Christina G. Waldman, JD, turns up a wealth of clues through her own original research and discusses the evidence presented by other researchers who have examined this play, all pointing to striking similarities between Bacon's life work and the legal theme at the heart of The Merchant of Venice. She identifies parallels in Bacon's writing and personal notes that preceded "Shakespeare" in coining many terms, and she deciphers numerous puns and intriguing possible historical precedents for names and symbols in the play, adding layers of appreciation and pleasure to the reading.

The author is licensed to practice law in New York State and writes for publishers in the legal field. She has had a life-long love of books and etymology. Her joy in sharing the wonder of words and stories shines through in every page.

|

|

About the Book

Could Bacon be Bellario in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice? This is the first book-length exploration of the mysterious Bellario, the old Italian jurist whose advice Portia seeks out. Because he is too ill to appear in court, he introduces Portia...

Could Bacon be Bellario in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice? This is the first book-length exploration of the mysterious Bellario, the old Italian jurist whose advice Portia seeks out. Because he is too ill to appear in court, he introduces Portia who appears in court his stead, taking the name of her male servant Balthazar. The play gives very few clues about Bellario's identity.

In a book published in 1965, Mark Edwin Andrews asserted that Francis Bacon was Bellario. Andrews argued not only that the author of the play The Merchant of Venice demonstrated vast knowledge of English jurisprudence and judicial systems, but that the play itself must have made legal history twenty years later, in 1616, in the case of Glanvill v. Courtney, by influencing two out of three of the top lawyers involved, a case with uncanny parallels to the play's courtroom drama with Shylock. Indeed, it was Francis Bacon who observed, "It partakes of a higher science to comprehend the force of equity that has suffused and penetrated the very nature of human society." Might he not have played a central role in bringing Equity into English jurisprudence?

As part of the Shakespeare authorship argument, this book explores whether Bellario was modelled on Francis Bacon - or whether Bacon, as the real author of the play, could have modelled Bellario on himself. Bacon was an innovator and reformer, an original thinker whose ideas helped pave the way for the modern world. Because Bacon took "all knowledge to be his province"Â and his genius touched upon many areas, this book explores a wide range of topics; for example, law, history, philosophy, linguistics, rhetoric, theology, and overlaps, such as the historical connections between law and literature.Â

Countless "coincidences" or matches are found between words coined by Bacon and Shakespeare, and the characters' very names suggest a wealth of punning, which the Elizabethans considered an art form. Further, she suggests the play should be understood as being set in 12th c. Venice, where Roman (civil) law was practiced - and that is what Bacon, who was tasked by the Queen to modernize the legal system, sought to introduce in London.Â

It is hoped this book will appeal to students of history, literature, law and pre-law, theatre, and legal historians, to students of Bacon and "Shakespeare" at a variety of levels, and to lawyers as well, who - as Daniel Kornstein predicted - all seem to eventually make their pilgrimage to The Merchant of Venice,

|

Preface

From the Foreword by Simon Miles, Manchester, UK

. . . Does it really matter who wrote the Shakespeare plays? There's an old joke about the works being written by another man with the same name; there's a grain of truth in that. The point hidden...

From the Foreword by Simon Miles, Manchester, UK

. . . Does it really matter who wrote the Shakespeare plays? There's an old joke about the works being written by another man with the same name; there's a grain of truth in that. The point hidden behind the gentle mockery of the authorship debate in this quip is this: what does it matter whether it is this man or that man, with the same name or a different name? Surely the works stand on their own, and it is a pointless waste of time to speculate on whether his identity is known, or concealed, or substituted.

They do, and it is. If it were simply a question of this man or that man, then it would be neither here nor there. But the authorship question does matter if the knowledge of the identity of the true author can inform and expand our understanding of the Works.

This is the litmus test. The only point in knowing the identity of the author of the Shakespeare works is to shine light on the works themselves.

If this is true, and surely it is, then the only authorship discussion that is of value, and worthwhile engaging with, is one that by offering an appreciation of the true author, their identity, life, career, thought, and writings, allows a deeper appreciation and understanding of the works of Shakespeare themselves. By these criteria, Christina Waldman's book passes the test with flying colors.

It takes as its starting point the open-minded possibility that Francis Bacon was the author of The Merchant of Venice, a fruitful location from which to begin the exploration as it turns out. Armed with Mark Edwin Andrews' penetrating insights, but now freed from the constraints of the orthodox authorship position, Christina Waldman has produced a welcome and timely contribution to the literature on Shakespeare's place in legal history. At the same time, Francis Bacon's complex relationship with The Merchant of Venice is illuminated by a richer perspective in this engaging study.

Simon Miles

Manchester, UK

|

More . . .

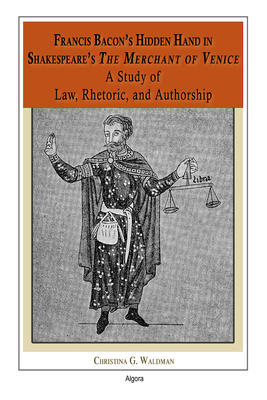

On the Cover Photo

The appealing illustration of a medieval merchant, coin in one hand and scales in the other, on the cover of this book, Francis Bacon's Hidden Hand in Shakespeare's 'The Merchant of Venice', is from an illuminated manuscript thought to be the first encyclopedia produced by a woman. The Hortus Deliciarum (Garden of Delights) was created by Herrad of Landsberg, Abbess of the Hohenburg Abbey (Mont Saint-Odile, Strasbourg, Alsace), for the edification and, as the title says,...

On the Cover Photo

The appealing illustration of a medieval merchant, coin in one hand and scales in the other, on the cover of this book, Francis Bacon's Hidden Hand in Shakespeare's 'The Merchant of Venice', is from an illuminated manuscript thought to be the first encyclopedia produced by a woman. The Hortus Deliciarum (Garden of Delights) was created by Herrad of Landsberg, Abbess of the Hohenburg Abbey (Mont Saint-Odile, Strasbourg, Alsace), for the edification and, as the title says, delight of the novices of her convent. The Hortus Deliciarum is a compendium of classical and Arabic texts, interspersed with music and poetry set to music. At least some of the poetry was written by the Abbess herself, addressed to the nuns. There are 336 illustrations. This unique book was destroyed by bombing in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. Fortunately, copies of the illuminations and text were made in the nineteenth century.

Twelve of the illuminations, taken from the "1818 Engelhardt facsimile," may be viewed at the Internet Archive through an external link in the Wikipedia article: Hortus deliciarum. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hortus_deliciarum to the Bibliot¨que Alsatique du Cr©dit Mutuel (Museum of Alsace), "L'Hortus Deliciarum, Planche 1." (https://web.archive.org/web/20110720213646/http://bacm.creditmutuel.fr/HORTUS_DELICIARUM.html.

Click on the first image and go to Fragments 5, 6, and 7. The French text is translated by Eliza Waldman here: Figures are part of a miniature that shows Christ chasing the unworthy out of a temple:

"¢ a commercial moneylender, holding a scale in his hand, cited in the text as Judas marchand.

"¢ a robber.

"¢ an entwined couple, labeled "An amorous young man, embracing his sweetheart."

According to art historian Meyer Shapiro, the text that appears alongside the miniature is a paraphrase of verses written by St. Peter of Omer. Here is the Latin: Judas mercator pessimus significat usurarios quos omnes expellit Dominus, quia spem suam onat in diviciis et volunt ut nummus vincat, nummus regnet, nummus imperat.

What does the Latin Judas mercator written above the merchant's head mean? (Judas marchand in French, as above.) "Judas"Â does not mean "Jewish."Â The word "Jew"Â did not derive from "Judas"Â but from "Judah"Â and "Judea."Â "Mercator"Â means "merchant or trader."Â The innocent-looking merchant depicted in the tableau as the personification of avarice is not necessarily Jewish.

Abbess Herrad would undoubtedly have been familiar with the Latin phrase Judas mercator pessimus. It occurs in the liturgy for the Easter Vigil, in the Tenebrae Responsories for Maundy Thursday (Second Nocturne for the Fifth Responsory). This is a pre-Vatican II service that dates back at least to the ninth century. It is based on teachings as old as the fourth century. The phrase means "Judas, the worst of all possible merchants."Â The words "Jew,"Â "Judas,"Â and "usury"Â were often used metaphorically; unfortunately, not generally in a positive way.

The idea of Judas mercator is tied up in a complicated way with Judas Iscariot, the apostle who betrayed Christ, delivering him into the hands of the Roman soldiers for thirty pieces of silver. That was his vile trade.

Herrad was a reformer. She was interested in stamping out avarice, particularly within the Church. But, while the idea of "cleansing the temple"Â was important, so was the teaching that Christ's cleansing and mercy were available for all, including the Barrabas-like "robber"Â and young couple in love ("fornicators"Â).

The Judas Mercator pessimus liturgy was rarely set to music. However, in Shakespeare's time, it was set to music twice, first by the Spanish Fr. Tom¡s Luis de Victoria of Spain (1548-1611) in 1585, and then by the Italian composer Carlo Gesualdo in 1611. Victoria is said to be the most significant composer of the Counter-Reformation in Spain.

Claire Asquith has observed that the language in The Merchant of Venice, in the "In such a night"Â scene with Jessica and Lorenzo, is reminiscent of language in the Easter Vigil liturgy. While there were few Jews in Alsace in 1167 when Herrad was just beginning to work on the Hortus Deliciarum, that would soon change. Beginning in the early twelfth and throughout the thirteenth centuries, Jews began to populate Europe. World trade was growing in importance. Jewish merchants had an advantage over Christian merchants, for they could act as go-betweens between the Muslim and Christian worlds, although they were accepted by neither.

Although usury violated Jewish as well as Christian precepts, some Jewish scholars found a way to argue around that, and money-lending for interest became one of their widespread activities. And yet, interestingly, "The prohibition and detestation of usury appear finally to be more a metaphor of economic and civic exclusion rather than the result of a specific ecclesiastic or civic opposition to Christian credit transactions."Â

References:

de Victoria, Tom¡s Luis, "Iudas mercator pessimus," transcribed and edited by Nancho Alvarez, http://tomasluisdevictoria.org.

Gallwey, S.J., Father P., The Watches of the Sacred Passion: With Before and After, third ed., vol. 2 (London, 1896), p. 17. Note, also, on that page, the reference to Daniel with Return to judgment, for they have born false witness. Daniel, from the story of Susannah and the Elders, is invoked by Shylock in The Merchant of Venice (IV, 1, 2164, 2281, 2288). www.opensourceshakespeare.org.

Green, Rosalie, Michael Evans, Christine Bischoff, and Michael Curschmann, Herrad of Hohenbourg, Hortus Deliciarum (London: The Warburg Institute, 1979).

Griffiths, Fiona, The Garden of Delights: Reform and Renaissance for Women in the Twelfth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

"Herrad of Landsberg," Catholic Online, Catholic Encyclopedia, copyright 2018. https://www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/view.php?id=5726. "Hortus Deliciarum," https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hortus_deliciarum and external link, "Hortus Deliciarum Copie de Christian Maurice Engelhardt, 1818," Bibliot¨que Alsatique du Cr©dit Mutuel, https://web.archive.org/web/20110720214243fw_/http://bacm.creditmutuel.fr/HORTUS_PLANCHE_1.html.

Hortus deliciarum, #0058012, The Granger Historical Picture Archive, NYC, 25 Chapel St., Brooklyn. https://www.granger.com/results.asp?search=1&screenwidth=1024&tnresize=200&pixperpage=40&searchtxtkeys=hortus%20deliciarum&lstorients=132.

"Judas Mercatur [sic] Pessimus,"Â 2002-2018, with sheet music and a link to a performance, https://www.traditioninaction.org/religious/Music_P000_files/P021_JudasMercator.htm.

Katz, Stephen, "Stephen Katz on Jewish Life in Medieval Europe,"Â Aitz Hayim Center for Jewish Living, transcribed by Neesa Sweet, 2014, http://www.aitzhayim.org/jewish-life-in-medieval-europe/. Open Source Shakespeare, www.opensourceshakespeare.org.

"Responsories for Holy Week,"Â https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Responsories_for_Holy_Week.

Shapiro, Meyer, "From Mozarabic to Romanesque in Silos,"Â (New York: College Art Association of New York, 1939), https://thecharnelhouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/meyer-schapiro-from-mozarabic-to-romanesque-in-silos.pdf.

Student William Clark "Herrad of Landsberg, A Medieval Woman's Companion, European Women's Lives in the Middle Ages," website of Susan Signe Morrison, author of A Medieval Woman's Companion, European Women's Lives in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2016), https://amedievalwomanscompanion.com/herrad-of-landsberg/. Todeschini, Giacomo, "The incivility of Judas. "Manifest usury as a metaphor for the Ã?â'¬Ã??infamy of factÃ?â'¬'¢ (infamia facti)" in J. Vitullo and D. Wolfthal, edd., Money, Morality and Culture in Late Medieval and Early modern Europe (Aldershot: Ashgate, forthcoming), pp. 1-22, http://www.academia.edu/2376304/The_incivility_of_Judas._Manifest_usury_as_a_metaphor_for_the_infamy_of_fact_infamia_facti.

|

More Information

Building on the work of Mark Edwin Andrews

Mark Edwin Andrews produced a remarkable exploration of law and equity in The Merchant of Venice in which he argued two things: that Shakespeare had a vast and profound knowledge of the English judicial system, and that the play The Merchant of Venice actually influenced that system, by influencing the results in a court case twenty years later. In Glanvill v. Courtney, a centuries-long battle for jurisdiction between the courts of law and equity...

Building on the work of Mark Edwin Andrews

Mark Edwin Andrews produced a remarkable exploration of law and equity in The Merchant of Venice in which he argued two things: that Shakespeare had a vast and profound knowledge of the English judicial system, and that the play The Merchant of Venice actually influenced that system, by influencing the results in a court case twenty years later. In Glanvill v. Courtney, a centuries-long battle for jurisdiction between the courts of law and equity came to a head and was resolved ;Â for a time.

He also pointed out the similarity between Portia's "quality of mercy"Â speech and the speech Sir Bacon drafted for King James for his 1616 decree resolving the dispute over jurisdiction. To this, Christina G. Waldman has added what appears to be an even parallel from a speech Bacon made before Parliament.

Andrews was writing as a law student taking a summer Shakespeare course in 1935, a time when the authorship of "Shakespeare"Â by the Stratford actor was simply not contested by serious scholars. It was supposed to have been a two-week project. Waldman has picked up where Andrews left off, using his extensive, meticulous research as a jumping-off place.

Entwined in Andrews;¢ arguments is his assertion, essentially ignored by scholars, that Bellario, the old Italian jurist who guides the action in the play by his pre-trial advice to Portia, is none other than Francis Bacon himself. Moreover, based on her own findings, Waldman persuasively suggests that someone more than an average English lawyer/playwright, apparently Francis Bacon himself, played an authorship role in The Merchant of Venice.

Today, Shakespeare's knowledge of law is no longer contested, although where he obtained it has still not been explained under orthodox theories. Waldman has searched for clues within the play itself and within the works of Francis Bacon to explore connections between Bacon and Bellario.

The relationship between Bacon and Bellario has apparently never before been explored, and Bacon's contributions to Anglo-American (if not the world's) jurisprudence have been largely been overlooked in recent times. Waldman found only one reference to a potential real-life model for Bellario, Keeton's remark that Karl Elze suggested Shakespeare may have had in mind Otto Discalzio, a 16th century Paduan jurist.

Andrews argued the play was set in 16th century England, in a common law courtroom, and that the last half of the play seems to switch from common law jurisdiction ;Â as if it were being tried in the court of King's Bench ;Â to equity jurisdiction ;Â as it were being heard in Chancery, but it was all happening in the same courtroom. That would not have happened in 16th-century England.

Waldman realized the setting should be understood as 12th-century Venice, not 16th-century England, although it's likely Shakespeare intended the comparison to be made, to write something that would be useful to his own day and age. Bacon was very much an advocate of practical knowledge, and he was a student of comparative law and legal history, history in general, pretty much taking all knowledge to be his province, as he said.

Waldman was able to search the plays and the works of Bacon online in a way not available to Mark Edwin Andrews in 1935. Today, no one contests the abundance and accuracy of the law in Shakespeare, but no one can explain it if Bacon's authorship is ruled out. Waldman's book shows that the appreciation of law in The Merchant of Venice is deeper, of a higher order, than just common law or civilian procedure.

The research Andrews did is amazing, finding cases in the old Year Books that bore relevance to Merchant. His work was praised by several Shakespeare scholars as well as by two United States Supreme Court judges. He posed the question but left it for someone of another generation to follow up and explore it in greater depth.

Maybe now, 400 years after the play was written and 80 years after Mark Edwin Andrews wrote his book, we can decipher some of the most telling clues.

|

Why Did Elizabeth Winkler Not Interview Any Baconians? - A Note from the Author | More »

Why Did Elizabeth Winkler Not Interview Any Baconians? - A Note from the Author

Something must be said about Elizabeth Winkler’s new book, Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies, in which she sets out – one would assume – to accurately and fairly present the current status of the Shakespeare authorship controversy. This would be a worthy goal. However, although she, an American journalist, interviewed people who might colloquially be called “Stratfordians,” “Oxfordians” (three of them), a “Marlovian,” general Shakespeare authorship doubters, and at least one indifferent, she did not interview any currently researching and writing Baconians! With the internet, we are not that hard to find. Unfortunately, this omission may mislead readers unfamiliar with the topic into assuming no one believes Bacon may have written Shakespeare anymore, or that no one is currently researching the evidence. Perhaps she would like to visit SirBacon.org which has recently hosted “The A. Phoenix PDF Library of Works." Yes, Winkler interviewed Mark Rylance the Shakespearean actor, but he did not come across in her book as a “Baconian” per se, but rather as a general doubter and, perhaps, “the most prominent person championing the idea of female authorship today” (p. 279). Even James Shapiro in his 2010 book Contested Will (Simon & Schuster) pointed readers to two resources for further reading on the case for Bacon: SirBacon.org and the (now late) Irish humanist Brian McClinton’s book, The Shakespeare Conspiracies: A 400-Year Web of Myth and Deceit (Belfast: Shanway Press, 2008). There are other books, of course, that could be mentioned, such as the late British barrister N. B. Cockburn’s The Bacon Shakespeare Question: The Baconian Question Made Sane (740 pp., 1998), Peter Dawkins, The Shakespeare Enigma (London: Polair Press, 2004), and my own, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice: A Study of Law, Rhetoric, and Authorship (New York: Algora Publishing, 2018). It is interesting that Winkler and Shapiro’s publisher is Simon & Schuster, publisher for the Folger Shakespeare Library which has long held to a “Stratfordian” view, although they have stated that “no one knows what “Shakespeare’s handwriting looks like.” Except, that may not be true, for the highly-respected forensic expert Maureen Ward-Gandy in her 1992 report determined, to a high degree of probability, that a play fragment found in binder’s waste in a 1586 copy of Homer’s Odyssey (It was a draft scene analogous to The First Part of Henry the Fourth) was in Francis Bacon’s own handwriting. It is printed in full for the first time in my book, and is also now available at SirBacon.org) (“The Northumberland Manuscript: Bacon and Shakespeare Manuscripts in One Portfolio!”). She reported Oxfordian interpretations of the evidence, related by Oxfordians she interviewed, as if they were the only interpretations – unaware of, or considering there might be, other interpretations. For example, she discusses Hall and Marston’s allusions to “Labeo” in their 16th century satires. There are several Labeos. Winkler knows of the poet Labeo, Labeo Attius (67-68), but not, apparently, of the great Roman jurist, Marcus Antistius Labeo, whose life parallels Bacon’s in notable ways (see my book, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand, pp. 99-100). The Latin words labefacio (to cause to shake, to totter) and labefacto (to shake violently) make an interesting association with the name, something Virgil and other writers of his time used to do. (See James J. O’Hara, True Names: Vergil and the Alexandrian Tradition of Etymological Wordplay (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press 2017 [1996]). It seems Hall and Marson were on to this rhetorical device as well. Arguably, any connection between Shakespeare and the law is one which points strongly to Francis Bacon, more than to any other “candidate” for Shakespeare authorship. Even Tom Regnier, the late “Oxfordian” researcher and a lawyer, has acknowledged the obvious, that Bacon’s legal accomplishments were much greater than Oxford’s (Thomas Regnier, “The Law in Hamlet: Death, Property, and the Pursuit of Justice (2011),” reprinted in Shakespeare and the Law: How the Bard’s Legal Knowledge Affects the Authorship Question, edited by Roger A. Strittmatter (June 2022), 231-251, 231. And no, Strittmatter did not make reference to my 2018 book, either.). Bacon devoted much of his life to making lasting legal reforms to English law. He was a wise visionary humanitarian, arguably not the “stodgy old philosopher” Edward J. White saw him as, in trying to persuade readers that Bacon could not have been Shakespeare, ironically, while at the same time detailing all the law in Shakespeare in his Commentaries on the Law in Shakespeare (St. Louis: F. H. Thomas, 2d ed. 1913, a book in which he was presumably much assisted by a woman Shakespeare lecturer, Mary A. Wadsworth, to whom he dedicated the book. Today she would probably be given co-authorial status.). Winkler also left important information out of her historical treatment. For example, in naming “Baconian” authors, she left out Constance Pott, founder of the Francis Bacon Society in 1866. Pott is the author of the first edition of Bacon’s writer’s notebook, the Promus, with all of its Shakespeare parallels. Did she mention Baconiana, the journal of the Francis Bacon Society (FBS) which has published the literary and historical research of its members since 1866? It can be accessed from the FBS website or SirBacon.org. A bibliography would have helped this book. SirBacon.org provides lengthy bibliographies of Baconian scholarship. She left out so many good writers. “It is hard to remember all, ungrateful to pass by any.” –Francis Bacon. Arguably, if you only look where the light is shining, you won’t see what is hidden in the dark. Bacon was not just any nobleman penning poetry and plays. If the reason for the secrecy is because it was Bacon and we don’t look into the matter deeply enough, we will never solve the mystery. I am not saying Bacon was the only writer, but it is illogical to assume this stellar writer, a major literary figure in his time, did not play a role. The word “author” can be used in a broader sense for the person in charge of a large-scale literary project. Abbess Herrad of Hohenbourg referred herself as the “author” of the Hortus Deliciarum, a twelfth century encyclopedic work she compiled for the edification of the nuns at her convent, although she herself wrote relatively little of it (see Fiona J. Griffiths, The Garden of Delights: Reform and Renaissance for Women in the Twelfth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007). In truth, there is no logical, factual reason that would make Bacon’s authorship of Shakespeare a factual impossibility. The two reasons that are usually given do not hold up under close scrutiny. Contrary to what is often said, for much of his life, Bacon did have the time to write plays and poems (and he had his “good pens” to help him). It was only after his cousin Robert Cecil died, during the reign of King James, that he was burdened with public office. Moreover, it is not fair to compare a person’s prose works with their poetry. Of course, there will be a difference in style! A person varies his/her/their writing style depending on what they are writing. One would especially expect this of a skilled writer, which Bacon was. James Shapiro observed in Contested Will that the only genre of writing at which Bacon did not try his hand was play-writing. Isn’t that interesting. James Spedding, Bacon’s nineteenth-century biographer and editor, observed that Bacon had the “fine phrensy of a poet,” intriguingly using Shakespeare’s phrase (see OpenSourceShakespeare.org). Not all Baconians think alike. I can speak only for myself. The truth does not have a label or denomination, to make a religious analogy. But all who are researching need to keep an open mind. It is the facts that matter. In fact, it was Bacon who helped develop the modern meaning of what a valid fact is (See Barbara Shapiro, A Culture of Fact: England, 1550-1720 (Cornell University Press). He wrote about the “four idols” that keep us from seeing things as they really are in his New Organon. Jesus spoke of such things as “motes” in our eyes. Bacon called them eidola from the Greek (hence informing his use of the word “idol”). If people do not look into the case for Bacon deeply enough, I fear they risk trying to solve a puzzle that has missing pieces. This is a scholarly subject. It is unfortunate that a journalist, by not interviewing Baconians and giving their case equal time, did not present the Shakespeare authorship controversy as it stands today fairly and accurately. The Baconians were the first to challenge William Shaxpere of Stratford’s authorship. Many of the arguments of the Oxfordians are derivative of those first posited by Baconians (e.g., Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford was a ward of Lord Burghley? So was Francis Bacon, after his father died in 1579. Burghley was Bacon’s uncle). Critical thinking is imperative. If readers do not have sufficient background in the history of a topic such as this, they risk being misled. If you are looking for something that has been intentionally buried, you have to dig deep. Granted, Winkler’s undertaking in this book was ambitious, and the goal of publicizing the aberrant “wall” against challenging the authorship of Shakespeare is worthy. The book seems to have touched a chord and to be have been well-received, generally, for the most part (by non-“Stratfordians,” at least). However, the reading public trusts those who write books to objectively give them the whole story; or at least refer them to other sources where they might find it, because no one writer or one book can do it all. Perhaps Winkler will agree with me that, the more we learn about this topic, the more we realize how much more there is to learn. However, getting better acquainted with all of Francis Bacon’s works is well worth the effort, in my opinion. July 5, 2023

|

|

Pages 376

Year: 2018

LC Classification: PR2944.W25 2018

Dewey code: 822.3/3;Âdc23

BISAC: LIT015000 LITERARY CRITICISM / Shakespeare

BISAC: LIT013000 LITERARY CRITICISM / Drama

BISAC: LAW060000 LAW / Legal History

Soft Cover

ISBN: 978-1-62894-330-6

Price: USD 25.95

Hard Cover

ISBN: 978-1-62894-331-3

Price: USD 36.00

eBook

ISBN: 978-1-62894-332-0

Price: USD 25.95

Mobi - for Amazon's Kindle

ISBN: 978-1-62894-332-0

Price: USD 25.95

|